The Happy Accident of the Fumé Dial

Oct 7, 2022

One of the pleasing things about working with vitreous enamel is its light-refractive qualities. Even the most opaque enamels have a particular vibrancy and depth of colour due to this quality. At the other end of the scale, transparent enamel gives you a vivid, jewel-like surface, which you can layer over engraved patterns that ripple through from beneath. Since we started, that’s something we’ve loved experimenting with; and as it happens, it’s an area where we’ll have some exciting new things to talk about very soon.

It’s also how we stumbled upon the technique for which a lot of people know anOrdain best: the ‘fumé’ enamel dial, introduced exactly three years ago in the original Model 2. It was transformative for us, and back in 2019, it was something we'd never seen realised in enamel. Today, however, it's a different story, with one or two other high-end brands employing the technique to make their own version. In the spirit of our discovery’s three-year anniversary, we thought we’d tell you a bit more about how we stumbled upon it.

Fumé is of course a Swiss-derived term, used for dials that show a smoky gradient effect – bright at the centre, fading to a shadow around the edges. This was popular in watches in the 1960s and ‘70s and it’s come heavily back into fashion in recent years, though it isn’t something we were specifically looking for when we discovered how to do it. In fact, it all begins with one of the most common problems you face in enamelling: the issue of warpage.

It’s a fact that when working with materials designed to react under intense heat, things can very easily get bent out of shape. Allow Sally Morrison from the enamelling team to explain: “It’s about coefficients of expansion: every material has a different rate at which it expands and contracts under the influence of heat. In enamelling, the struggle you always have is that the dial substrate has a different coefficient to the glass enamel that’s going onto it, so they’re pulling and pushing each other. That means it’s very easy to end up with warped dials.”

The team had used transparent enamels on copper before; this provided an inky depth, seen on the original Model 1’s Translucent Blue, and the original Model 2’s Midnight Green. Often though, the copper base proved too dark to do justice to the vivid, stained-glass tones of transparent enamel, as these enamels tend to be more impactful on a precious metal base.

Left: Model 1 Green Fumé. Right: Model 2 Midnight Green.

We started our experimentations using transparent enamels on silver in 2017, but found that the metal warped far more than we were used to: as the dials went through the enamelling process, they’d warp upwards in the centre, forming a domed effect. When we ground the enamel flat on top, we discovered a remarkable effect: since the transparent enamel was now deeper and therefore darker at the edges and shallow at the centre, it serendipitously formed a fumé effect.

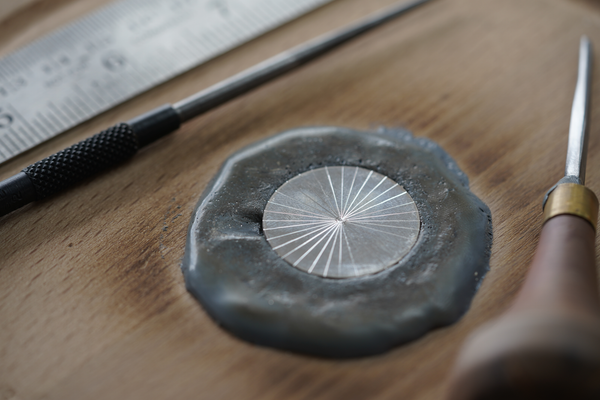

We’d discovered an aesthetic we loved, but this wasn’t going to be a practical thing to reproduce, not least because the back of a dial needs to be flat to fit neatly with the movement beneath it. The problem was that we had no idea how to make a minutely domed silver dial, or who would be able to make one for us. But we had a stroke of luck: the watchmakers Craig and Rebecca Struthers put us onto a traditional toolmaker based (like them) in Birmingham’s historic Jewellery Quarter. With decades spent in artisanal metalworking, he was able to make the dial blanks (a process of die stamping a flat silver disc) to the minute tolerances we need.

The fumé dials each have around seven layers of enamel, and dealing with warpage remains the primary challenge in making these – from every batch of six we produce, we expect a couple of rejects. Bear in mind that from the top of the enamel surface to the back of the dial blank is only about 1mm; but the outside areas at the edges of the dome carry double the thickness of enamel compared to the centre. The tensions created when applying heat, therefore, are considerable, though as time has gone on we’ve learned more and more how to work with this.

“An element of warpage is actually now factored into the process: the enamel pulls and pushes the blank, so that you arrive at a flat result at the end,” says Sally. “Eventually you get a kind of intuition about working with the enamel and understanding how it performs, particularly since every colour reacts differently. It’s one of the difficulties we have teaching new enamellers – you have to kind of become one with the enamel…”

She’s only half joking.